Christopher Whittick gave an interesting talk at Rye Museum on Thursday, May 10.

So much of the rich local history around us is visible – much admired by visitors too — but much of it is not. Thankfully, archivists as well as archaeologists can use the clues that remain to tell us much about what once was, as the latest talk at Rye Museum – every seat occupied – proved abundantly. Christopher Whittick, County Archivist at the East Sussex Record Office (ESRO), has been acquiring and cataloguing medieval deeds and manorial records for ESRO for over 40 years and sharing what they tell us, now at The Keep in Falmer, opened by the Queen in 2013 and acknowledged to be the most up-to-date local record office in the UK.

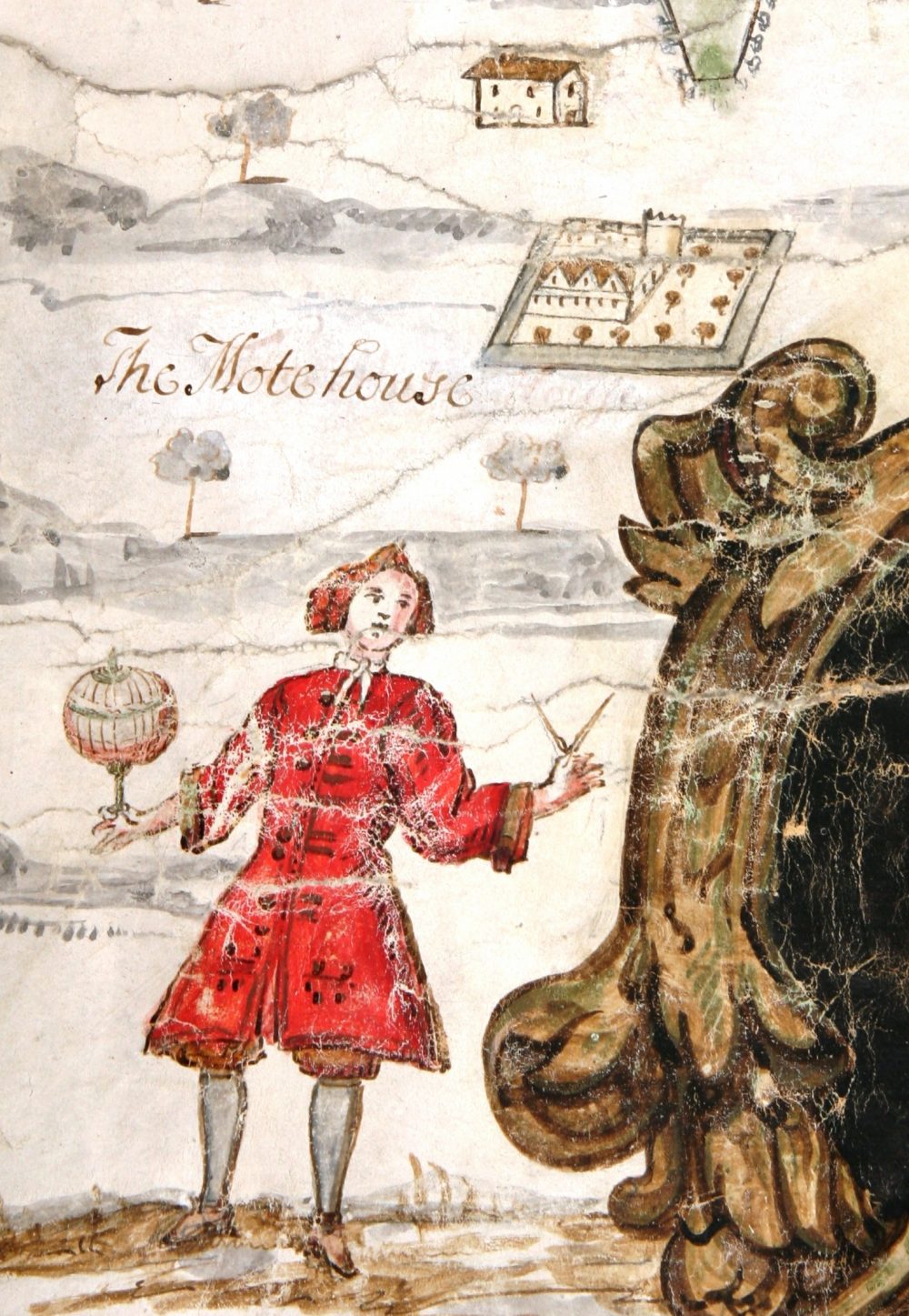

In 1952 at Lloyds Bank in Rye a collection of medieval documents was found relating to the manor of Mote in Iden, just three miles from Rye, and to the three important families who were lords of Mote: the Pashleys (1289-1458), the Scotts (1458-1646) and the Powells (1646-1765). The documents, in particular the 15th century account rolls, tell of the buildings which once stood within the mote, and the activities of the families responsible for them and the surrounding lands. They reveal an astonishing amount of information now available in book form (see below), highlights of which our speaker presented to us with splendid illustrations on screen.

We learned how much the accounts, written so neatly in Latin with some English – on paper probably stocked from Calais — tell us about the building works and their owners, particularly Sir John Scott, and their key roles in royal service, in the development of trade and as diplomats on both sides of the Channel.

There were insights into education, (and the unusual lack of it in one illiterate Pashley knight), rebellions and sieges, the need for defensive castles and towers against the French, the crucial importance of links with Calais and Flanders and of nearby Rye and Winchelsea as leading Cinque Ports, how early deaths leading to multiple marriages (and stepchildren) exacerbated rivalries (whether over inheritance or at Lancastrian vs Yorkist level, and sometimes leading to murder) every bit complicated as today’s divorces sometimes do. It was a fascinating immersion into provincial society at the end of the Middle Ages against a background of national affairs.

The 21st century audience was reminded that once it was much easier to travel from here by water than on roads– where they existed. We also appreciated anew the skills and initiatives of forebears who strived and sometimes even thrived without the knowledge, experience, communication and technology we take for granted today. We increased our knowledge of word origins too, ”indenture’ being just one example: it was a deed or agreement executed in two or more copies with edges correspondingly indented as a means of identification; a mismatch betrayed a would-be deceiver.

The Manor of Moat or La Mote first appears in 1318, when Sir Edmund de Passeley received licence to crenellate his dwelling place of La Mote. He had caused a huge basin to be excavated with an island in its middle for a castle to protect the rear approach to Rye from French invaders. There have been other buildings and even a harbour on the site over the centuries since but what remains today is the basin and two subsidiary motes, still impressive but sans buildings, and a small nature reserve whose frog chorus in June is reported to be quite loud. The site is now a scheduled monument considered of high archaeological potential.

Outstanding among the owners of the demesne and household at Mote was Sir John Scott who not only survived but thrived in the middle years of the 15th century. He was building a defensible tower in the late 1460s, conducted trade negotiations in Flanders which probably influenced him, unusually, to use brick as a building material. A time in Calais led him to appreciate the potential market for firewood and invest in its production and transport on a large scale, thus what we now know as Scotts Float near Playden; there followed a similar story with reed produced on the farm at Mote for roofing. Sir John owned several estates, and the list of his posts includes being Controller for Edward IV’s royal household.

It was in his time that parchment was being replaced by paper and he is known to have imported it from Calais for the accounts. English was interacting with Latin and he made frequent notes in the margins of the Mote rolls in both languages; he’d had a legal education. A third struggle of the times was between Catholicism — the Scotts –and Puritanism — the Powells, who became the next owners of the manor of Mote. While at Mote Nathaniel Powell purchased the manor of Bodiam ( built on much the same plan as the earlier Mote) and took an interest in manorial documents. It is probably thanks to him and his steward Richard Kilburne that the documents survived.

Rye Museum is known for its fascinating speakers, a number of whom have also written books sought by members of the audience. Such was the case this time. A book by Mark Gardiner and Christopher Whittick, Accounts and Records of the Manor of Mote in Iden, 1442-1551, 1673. (Sussex Record Society, 2011) can be purchased from the Museum for the special price of £10.

With thanks to Christopher Whittick for permission to use this and the other photos