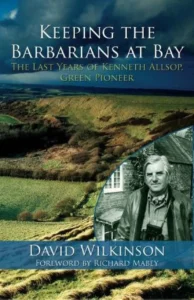

Rye News book reviewer Phil Mullane looks at the last years of the author, broadcaster and environmental campaigner Kenneth Allsop in “Keeping the Barbarians at Bay” by David Wilkinson.

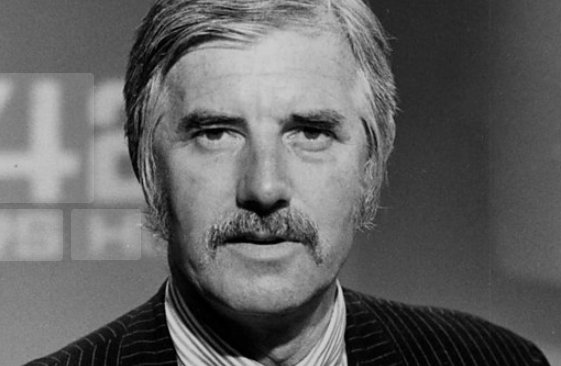

Until I came across David Wilkinson’s book I had all but forgotten the man. I remember Kenneth Allsop as one of the presenters on the ground-breaking BBC current affairs programme Tonight. It was broadcast on weekday evenings from 1957 to 1965 to plug the early gap between 6pm and 7pm called the toddlers’ truce when parents were supposed to persuade their children to go to bed. It was on this show that I first heard a young Bob Dylan sing With God on our Side.

Although it was television that made him a household name, Allsop was a prolific writer. In addition to his extensive journalistic output, he wrote numerous books including novels and literary criticism. Interviewed in 1972 Michael Parkinson asked Allsop what gave him the most pleasure. There was a pause. “Crouching in solitude late at night over a typewriter putting words down,” was his reply.

Allsop’s urbane manner, film-star good looks and received pronunciation coupled with his discerning insight into society, his love of jazz and fast cars made him one the nation’s early TV personalities — an accolade he hated. He appeared uncomfortable when Michael Parkinson referred to the fact that he was voted the world’s fifth most handsome man.

In the book Wilkinson, a respected ecologist, focuses on the early 1970s before the televising of parliament and well before concerns about climate change. It was a time when the IRA were bombing mainland UK and Mary Whitehouse, the saintly taste and decency campaigner, was striving to “get filth off the television”. Whitehouse famously berated the BBC for allowing The Beatles to use the word “knickers” on TV in 1967.

At that time Allsop’s environmental campaigning escaped my attention. Among his triumphs was a campaign to protect Dorset against oil drilling close to his newly purchased mill house in Dorset thereby saving 200 acres of primeval oak. Annoyed by a representative of the Forestry Commission responsible for the tree felling programme Allsop said: “You may think that I’m a busybody, Mr Rouse, but I think you are nothing but a wooden-headed timber merchant who can’t see the wood for trees. You know the price of matchwood, but the value of absolutely nothing.”

Allsop campaigned against Rio Tinto Zinc’s copper mining plans in Snowdonia and drew attention to the environmental devastation to the rain forest caused by the construction of the Trans-Amazonian super highway. In many ways Wilkinson’s account of the final years of Allsop’s life in the 1970s has echoes for us in the early 21st century. Recent plans to license new oil fields in the North Sea, continuing concerns about deforestation in Amazonia and the appalling state of British rivers and beaches are issues that Allsop, were he alive today, would certainly have highlighted through his trenchant campaigning journalism.

As a passionate ornithologist he would be incensed to read the 2022 RSPB report documenting the illegal widespread killing of hen harriers on grouse shooting estates today and be alarmed that, according to a devastating UN report on the state of nature, the world has failed to meet a single target to stem the destruction of wildlife and life-sustaining ecosystems in the last decade.

Allsop also hosted the programme Down to Earth but his approach soon proved too hard- hitting and radical for BBC management and it lasted only four months in 1972. The director general Charles Curran’s belief that BBC output should be “the vehicle of conformity” differed markedly with Allsop’s view that journalists should be in the business of “spilling the beans, not selling them”. On the scrapping of the show one journalist commented that “It is not just Down to Earth that they buried last night. It is a whole area of inquiring, investigatory journalism which we are now in danger of losing.” Such a comment rings even more true fifty-three years later.

Things came to a head. Thwarted in his campaigning journalism and battles with “the barbarians”, his disappointment and despair were exacerbated by the constant pain associated with an artificial limb and a recurring kidney complaint. He took his own life on May 23 1973 at the age of 53.

Keeping the Barbarians at Bay shines light on a man now respected as a pioneering conservationist and confirms Allsop’s place in the esteemed company of early naturalists like Gilbert White and Richard Jefferies and contemporary writers on the natural world like Robert MacFarlane and Richard Mabey.

Image Credits: BBC https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p009ncjz , David Wilkinson .