The Battle of Hastings, and specifically its location, has long been a matter of debate. Whilst the traditional location of Battle Abbey has much to commend it in terms of near contemporary historical accounts, the lack of archaeological evidence of the brutal and bloody conflict has understandably aroused doubts, writes Guy Harris.

Contending theories place the location at which the Norman and Saxon armies clashed, at Caldbec Hill, to the north of Battle, and at Crowhurst, to the south.

Now, a third compelling theory has been advanced by amateur historians – four brothers named Starkey. The brothers’ contention is that the Norman army pitched up not at Pevensey as traditionally understood, but at Cadborough, above our own dear Rye!

The theory continues that William advanced along the Udimore ridge and slugged it out with Harold at Sedlescombe. Could it be true? Might history be re-written? Well, read on and you decide. And should you feel convinced by the theory, you can help to prove it by declaring any archaeological evidence you might have found.

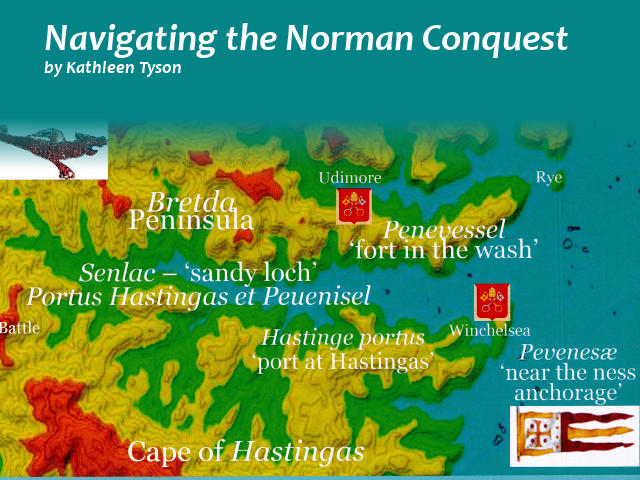

[Editor’s note: Rye News has reported before on the possibility that William the Conqueror landed near Rye, rather than at Pevensey, though that writer, Kathleeen Tyson, (her book cover is shown right) was uncertain where the Battle of Hastings might actually have taken place. These writers are more certain]

Jonathan Starkey takes up the story.

Norman Invasion Synopsis: We have a theory that the Norman army landed on the north bank of the Brede, then moved to Winchelsea where it stayed for two weeks before attacking and defeating the English army at Hurst Lane near Sedlescombe. We published a book about this in 2016, to coincide with the 950th anniversary – and you can find more information, and contact us, at www.momentousbritain.co.uk.

A landing along the River Brede might seem unlikely today, but the geography of the region was profoundly different in the 11th century when sea levels were higher. The river Brede was a substantial estuary in those days, nearly 1km across at high tide. This was also true of the river Ash Bourne to the west.

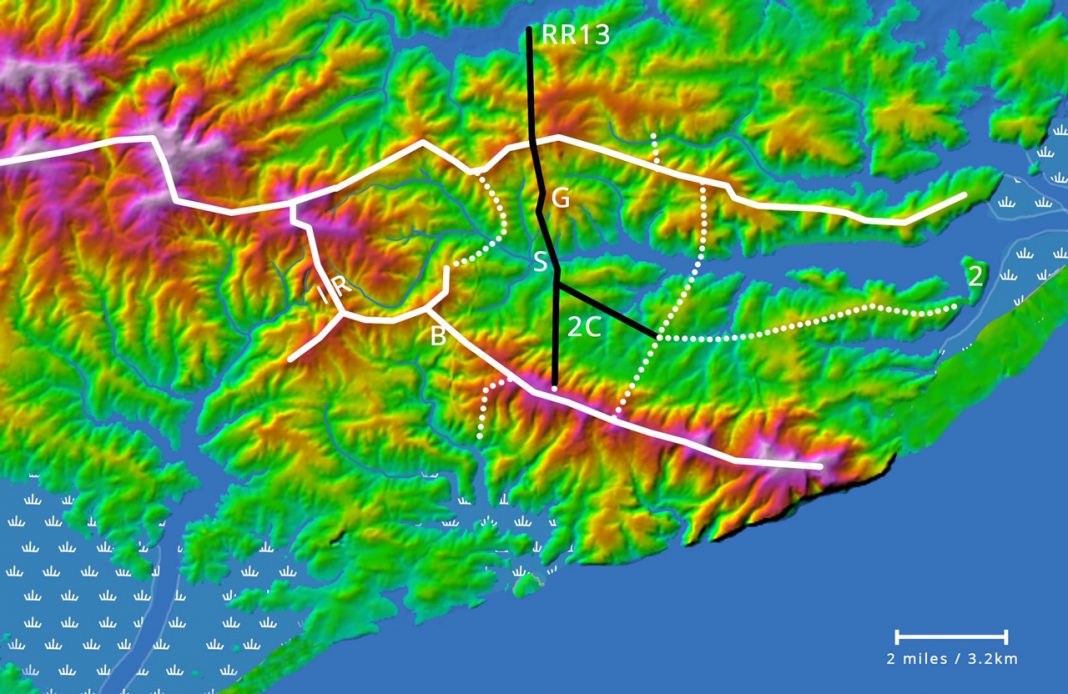

These two estuaries enclosed a physically distinct Hastings peninsula that was almost an island. Its isthmus (IR on map above) at what is now Sprays Woods on the Battle Road [the B2096 near Netherfield] was barely 600m across.

We think that William’s plan was to lure Harold to the Hastings peninsula and to ambush him at the isthmus or at Sedlescombe bridge (S on the top map) on the B2244, the only two crossing points that were viable for an army.

William placed himself and his barons at Winchelsea as bait, making every effort to appear inept, arrogant, toothless and siege prone. Meanwhile, his powerful cavalry would have been secreted at what is now Great Buckhurst farm (2C on the map), invisible from the other side of the river, yet able to swoop down on Sedlescombe bridge or the isthmus ridge if Harold attempted a crossing.

We guess that Harold sensed the danger. He camped the English army on Great Sanders ridge (G on map) , the last high ground on the Rochester Roman road (the B2244, marked RR13 on map) before the Brede and just north of Sedlescombe, while his scouts and messengers checked the other side for an ambush.

Harold thought the Great Sanders camp was safe because his spies and scouts had told him that the Normans were overwhelmingly footbound. They were wrong. William had brought a huge complement of several thousand knights and war-horses. Harold discovered the horrible truth the day after he arrived.

If he personally, or the English army collectively, tried to escape from their ridge, the Norman cavalry would catch them in open ground where they would have been annihilated. Harold chose instead to fortify the camp and await reinforcements. They did not arrive in time.

On the day of battle, Harold moved the English army 200m south onto a south-facing spur either side of what is now the NNW-SSE part of Hurst Lane, because it offered better protection against war-horses. Indeed, its defensive merits were so great that there was close to zero chance of a Norman victory, if only the English army had been better disciplined. But they lost – though where is any evidence?

Continued next week

Image Credits: Momentous Britain http://www.momentousbritain.co.uk/ , Kathleen Tyson , Chris Lawson .

A landing near Rye would make sense, because Rye was already in Norman hands in 1066 – the Town had been given to the Abbey of Fecamp in Normandy in 1035, and the Abbot of Fecamp is believed to have travelled over with William’s fleet. So a Norman fleet landing near Rye would have been unopposed by the locals as they were already subjects of the Normans.

That’s extremely interesting, Paul. Thanks for your input. ‘Friendly’ and possibly familiar territory… I did recently note a long depression at the top of the wooded ridge at Cock Marling. I wondered if that could possibly be evidence of a salt pan, as mentioned in Jonathan’s article…

The plot thickens!

Could it be possible that all three theories are correct?

I read of rough weather in the channel that September and am reminded of history tells us, confusion often comes out on top in wars. It is likely William’s ships became separated and made land at numerous locations. And that the Norman forces became fragmented as a result; so encountered the English at a number of locations? Perhaps the Normans used their displacement as an advantage by haranguing Harold’s weary army or its long caravan on its way down to the ‘main’ battle? Do let me know if this is a load of baloney.

This is the best theory I’ve read of where the battle took place. I’ve read the Starkey’s book, and also Nick Austin’s book on the Crowhurst theory, which am sorry to say is in my opinion extremely amateurish archeologically, jumping to way too many unsubstantiated conclusions, and eye-rollingly suspicious of conspiracy theory like motives of English heritage, though it was thoroughly enjoyable. I’ve walked the Crowhurst battlefield, and as far as possible the Hurst Lane one. Haven’t walked Caldbeck hill though. This issue of where the battlefield was is the most interesting historical mystery to me. One thing I feel totally certain is that it was not near Battle Abbey. Time Team’s program on the subject was also very interesting but they bottled it with their conclusion, which arguably has done a disservice to history as well as it was the highest profile recent investigation.

I would LOVE it if they found some archeological evidence at the Hurst Lane site!