This week in Rye News we’re publishing an article all about Rye from the Washington Times. The USA paper featured our town thanks to writer Andrew Salmon, who was brought up in Iden and returned to Rye recently after many decades. He is now the Washington Times Asia Editor based in Seoul, South Korea.

A fortress of twee holds back the UK’s national malaise, just barely

The United Kingdom is wracked by political and economic angst, but on its south east coast, a tiny fortress town famed for its medieval charm is – just – holding back the tide of national misery.

From afar, America’s closest ally looks solid. The UK boasts the world’s sixth largest economy, nuclear arms and a soft-power armoury stuffed with Shakespeare, the monarchy and Premier League soccer.

Close up, media and locals fret endlessly about “Broken Britain.”

Politically, Prime Minister Keir Starmer took power in 2024 on a blast of hope after his Labour Party overturned 15 years of majority Conservative Party rule.

He botched it. Per 2025 polls, he is Britain’s least popular premier ever, personifying widespread dissatisfaction with politics.

Economically, the promise of 2016’s Brexit – Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union – never materialized. Brits suffer sluggish growth, a cost-of-living crisis and disintegrating public services.

Socially, polarization runs deep with noisy debate – frequently toxic – focusing on immigration.

Seventy-eight miles south of central London, the town of Rye (population 4,800) both exemplifies and defies national trends.

Britain’s new politics

Labour seized Rye from the Conservatives in the 2024 election, but recent developments mirror Westminster shifts. In January, a town councillor slashed her Labour affiliation; last November, a nearby sub-constituency by-election was won by Aidan Fisher, representing MAGA-inspired Reform UK.

“Reform won the by-election because people have lost faith in the traditional parties,” said Mr. Fisher. “People don’t feel listened to and are extremely disillusioned.”

New parties are rising. No general election is expected before 2029, but Your Party now challenges Labour on the left, while Reform strives to replace the Conservatives on the right.

Per surveyor YouGov, Reform is leading national polls. It has led debate on one red-button issue.

“The main national issue residents raised with me was illegal immigration; people want something done,” Mr. Fisher continued. “[Mainstream parties] have promised to ‘stop the boats,’ yet the problem has only worsened.”

Rye’s local lifeboat has plucked wannabe migrants from the Channel, and 14 bolted from a vessel that beached nearby in 2022.

But in the town, immigrants are invisible, bar 15 Ukrainians sheltering from Russia’s invasion.

Quaint streets, hidden stresses

Backed by rolling countryside, Rye was both a hub for, and a victim of, cross-Channel raids during the 100 Years War, later becoming a hive of smuggling. It would go on to shelter both French Huguenots, and later, Belgian World War I refugees.

Today, Rye is renowned as one of the nation’s prettiest towns.

It boasts a 13th century castle, a 14th century fortified gate and a 15th century hotel, the Mermaid Inn, where guests including Judy Garland, President Eisenhower and Johnny Depp have braved its (alleged) ghosts.

The winding cobbled streets of Rye’s Citadel – lined with medieval, Tudor and Georgian architecture – are frequently used as period drama sets.

The main street features none of the empty storefronts that depress multiple UK town centres. Snug gift shops, galleries, cafes and pubs bear not a single global brand: virtually every business, run by cheery locals, is independent.

But shabby infrastructure makes reaching Rye tricky. There is no expressway from London, 78 miles distant; B roads are honeycombed with potholes; and trains are expensive and frequently cancelled.

Communal spirit makes up, somewhat for faltering public services. “In Rye, everyone is a volunteer,” said Rye News editor James Stewart.

Rye’s police station opens just 12 hours per week, but an informal community of “curtain twitchers” and a network of CCTV cameras installed outside its many Airbnbs, provide overwatch.

Local firefighters – many volunteers – successfully contained a 2019 hotel blaze that could have gutted the town.

“People look out for each other: it works,” said Rye Mayor Andy Stuart, speaking at the town hall, with its list of clerks dating to 1300. “But there’s always a need for more.”

Anticipating local government restructuring, Rye is bracing for further cuts. Britain’s much- lampooned bureaucracy, however, is alive and kicking.

Mermaid Inn proprietress Judith Blincow recalls facing legal sanction from fire authorities if she did not install modern safeguards – and from heritage preservation authorities if she did.

In the surrounding countryside, fruit farming has declined, with many European pickers departing with Brexit. Rye’s beleaguered fishing fleet faces larger foreign boats, tight quotas and hungry (and protected) seals.

Tourism is Rye’s main earner – a trend boosted by COVID. After international travel cratered, intra-UK tourism exploded. Rye, leveraging its innate charm, saw visitors surge.

Merchants benefit. Not all locals are happy.

“Rye has become a theme park!” sniffed one. “The shops here are for tourists, not us,” said a hotel receptionist. “We have to buy groceries in Hastings” – a town 12 miles distant.

Income inequality is stark.

Downtown is dominated by upbeat, Barbour-clad, dog-walking members of the middle class. But poorer locals are being driven out by pricey housing; an estate across Rye’s rail tracks is in the bottom 25% of the UK’s most deprived wards.

“Hospitality work does not pay hugely,” acknowledged Stuart.

“We are not a big town, we don’t have many things you pay money to go and see,” added Sarah Broadbent of Rye’s Chamber of Commerce. “Rye is experiential: it’s walking around the town.”

Still, one new rural sector is fermenting nicely. Fast-heating South East England is now home to vineyards which surround Rye on three sides.

“This may be the one upside to global warming,” said expatriate Norwegian Kristin Syltevik, who sold her IT company to establish winery Oxney Organic Estate.

She dates the maturity of the regional wine industry to around 2012; major French winemakers are investing.

Elsewhere, the countryside is grappling with the loss of its community pillars: pub and church.

Old traditions, new challenges

Pubs have, for centuries, been hubs of British community, but in 2025, were closing at “alarming” rates of one per day nationwide, driven by shifting drinking habits and high alcohol taxes.

Rye is served by a dozen pubs, but three nearby villages have lost theirs in recent years. Volunteers bought one back from the brink in January when villagers pooled resources to acquire their closed pub, set to re-open as a co-op.

The outlook for churches is equally murky.

In 2025, the Church of England trumpeted a 1.02% on-year rise in attendance. However, that represents only 1.05 million churchgoers – among England’s population of 58.6 million.

In Rye’s St. Mary’s, a January Sunday service drew just 50 congregants. Vicars are no longer assigned to outlying villages, but rotate around parishes.

The National Church Trust reported in 2025 that 3,500 churches had closed nationwide in a decade. Some have been repurposed as cafes and even night clubs; one near Rye has become a home, its garden the graveyard.

“I don’t know what the future holds for rural communities and culture,” fretted Christopher Breeds, a retired vicar. “It could change beyond recognition.”

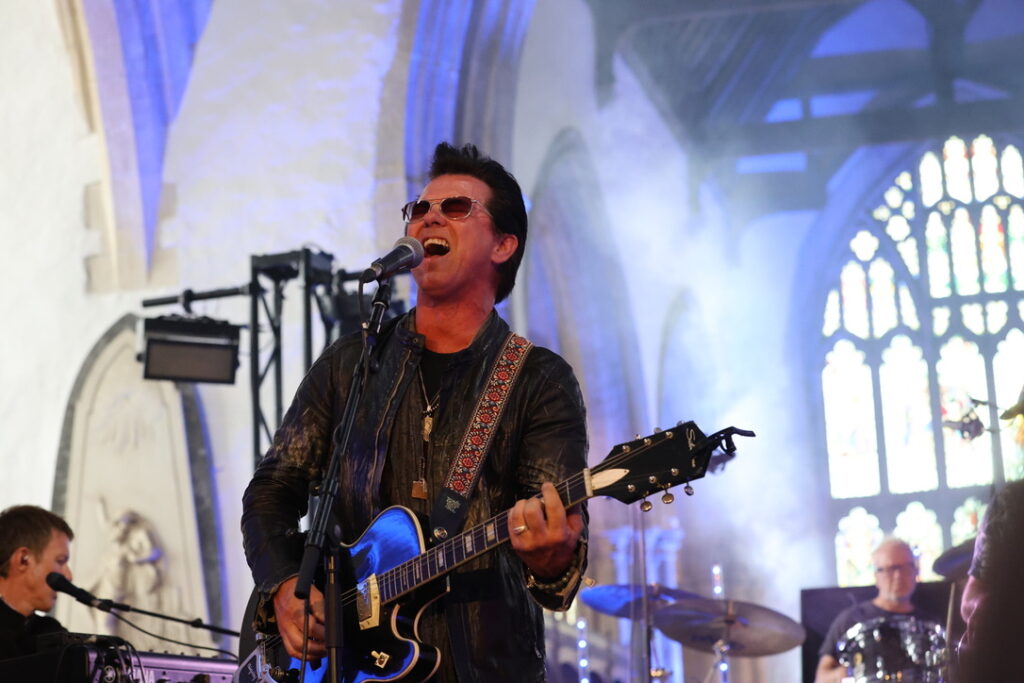

Rye church warden, Roy Abel, is more upbeat, noting that St Mary’s hosts choral evenings and jazz festivals.

“The church is a functional space,” he said. “Let the building work its magic!”

And enduring old-school decency comforts Rye’s current refugees.

“‘Rye’ is the Ukrainian word for ‘paradise,’” said Mayor Stuart. “Their expectations were high, but they were amazed that this is a paradise of calm and acceptance. It’s touching.”

Image Credits: Chris Lawson , Juliet Duff , Mermaid Inn , Kt bruce , Washington Times .